What Drove Buffett’s Early Outperformance

Lessons from Eight Investments in His Early Years

„My cigar butt strategy worked very well while I was managing small sums. Indeed, the many dozens of free puffs I obtained in the 1950s made that decade by far the best of my life for relative and absolute investment performance.“ - Warren Buffett

Quotes like this make Buffett’s early years sound almost effortless.

As if he was just flipping through Moody’s manuals, picking up one cheap stock after another. It creates the impression that any reasonably competent investor could have done the same.

But was it really that simple?

Take Benjamin Graham. Buffett’s mentor. The father of value investing.

Graham wrote The Intelligent Investor, co-authored Security Analysis, taught generations of investors, and ran multiple investment partnerships over decades. Buffett admired him deeply.

Yet Graham’s results never came close to Buffett’s.

In fact, Graham didn’t even beat the market for long stretches of his career. The Ben Graham Joint Account, which ran from 1925 to 1935, earned roughly 6% annually, barely ahead of the S&P 500’s 5.8%. His later and more famous fund, Graham-Newman Corp., actually underperformed from 1945 to 1956, earning around 15.5% while the S&P 500 delivered closer to 18.3%.

By comparison, Buffett absolutely crushed the market during his partnership years.

During his partnership years, from 1957 to 1969, he compounded capital at 29.5% per year, while the Dow managed just 7.4%.

So it’s clear that simply buying stocks below liquidation value cannot, by itself, explain Buffett’s early outperformance. If that had been enough, Graham should have achieved similar results just by buying net-nets.

So what was different?

To get closer to an answer, I want to look at some of Buffett’s early investments. Not just the outcomes, but the setups, the decisions, the position sizing, and, most importantly, what he did differently from Graham.

By doing that, a few key factors become visible that played a major role in Buffett’s outstanding returns. I highlight them at the end.

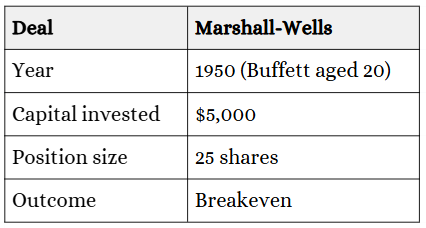

Marshall-Wells

In 1950, Warren Buffett was a 20-year-old graduate student at Columbia. One of the stocks he owned at the time was Marshall-Wells, then the largest hardware wholesaler in North America.

When Buffett heard that the company’s annual meeting was taking place just across the river in Jersey City, he asked his professor, David Dodd, whether he could skip class to attend. Dodd agreed.

Buffett went there not to be social, but to observe management. He wanted to see how they behaved, how they answered shareholder questions, and whether they took their owners seriously.

He didn’t like what he saw.

The meeting felt like a box to check for management. The directors acted as if shareholders were an inconvenience. Most of the attendees didn’t seem to care either. Buffett believed annual meetings should be moments of accountability, and this one clearly wasn’t.

Still, on paper, Marshall-Wells looked exactly like the kind of stock a young Buffett was searching for.

Shares traded around $200, earned about $62 per share, and sold below net current asset value. The balance sheet was loaded with cash and inventory, much of it non-perishable goods like tools and housewares. The company had been profitable for years and had grown steadily throughout the previous decade.

So Buffett sized the position accordingly.

While Graham-Newman held only a small position, Buffett loaded up and made Marshall-Wells a quarter of his net worth.

At that same shareholder meeting, Buffett also met Walter Schloss, who was asking sharp questions that made management uncomfortable. Buffett liked that. He introduced himself and was impressed to learn that Schloss worked for Graham-Newman.

Another investor at the meeting, Louis Green, later took Buffett out to lunch. That conversation became an important lesson. Green challenged Buffett on why he owned Marshall-Wells. Buffett gave a weak answer and said, more or less, that he owned the stock because Graham owned it.

In reality, that wasn’t true. Buffett had done his own work, which was exactly why he had attended the meeting in the first place. Still, Green wasn’t impressed and dismissed him.

Marshall-Wells never became a big win for Buffett. He sold the stock within a year, more or less at breakeven, and moved on.

The business later faced tougher competition as the hardware market changed, and the economics got worse. Even though the stock was cheap, it wasn’t the kind of situation that would drive Buffett’s best early results.

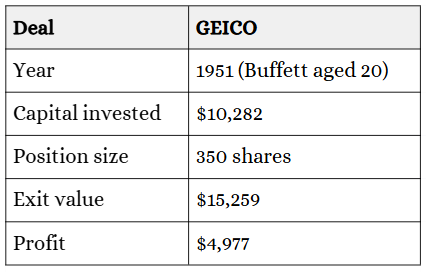

GEICO

By early 1951, Warren Buffett had absorbed everything there was to learn from his hero, Benjamin Graham. He had read Security Analysis several times, knew the case studies by heart, and already stood out in class. That year, Graham gave him an A+, the only one he ever awarded.

Around that time, Buffett noticed something interesting.

Ben Graham was the chairman of a small insurance company called GEICO. Graham-Newman had previously bought a large block of the stock at a classic Ben Graham price.

GEICO’s headquarters were in Washington. So one Saturday, Buffett took a train from New York down to Washington and knocked on the front door.

By sheer luck, the janitor let him in and mentioned that Lorimer Davidson, GEICO’s financial vice president, was in the building. Davidson would later become CEO, and he was also responsible for putting together the Graham-Newman deal.

There was no better person for Buffett to meet.

So, Buffett started asking him questions. Davidson kept answering them. And the conversation went on for hours.

By the end of that meeting, Buffett understood GEICO far better than most investors ever would. GEICO sold insurance directly to customers instead of using agents. That simple choice made it a much lower cost operator, with profit margins well above those of traditional insurers.

Still, GEICO was not a Ben Graham stock anymore. It traded at around eight times earnings. That was still cheap, but it wasn’t deep Ben Graham territory anymore.

Buffett believed GEICO could take market share from higher-cost competitors. If that happened, earnings per share would continue to grow over time.

So Buffett invested heavily.

He put roughly 75% of his net worth into GEICO, investing a total of $10,282.

Graham would never have allowed that level of concentration.

Here’s Buffett later, in The Snowball:

“Ben would always tell me GEICO was too high. By his standards, it wasn’t the right kind of stock to buy. Still, by the end of 1951, I had three-quarters of my net worth or close to it invested in GEICO.”

Why did Buffett do this?

He didn’t want a portfolio with one great idea and four decent ones, where only 20% of his money sat in his best opportunity.

If GEICO rose 50% and Buffett had 75% of his money in it, his net worth would increase by 37.5% just from GEICO alone. If he had spread his money evenly across five stocks, that same move would have increased his capital by only 10%.

Buffett wasn’t interested in compounding his money at 10%. He wanted to compound at 30% or 40%.

He sold the GEICO position the following year for $15,259.

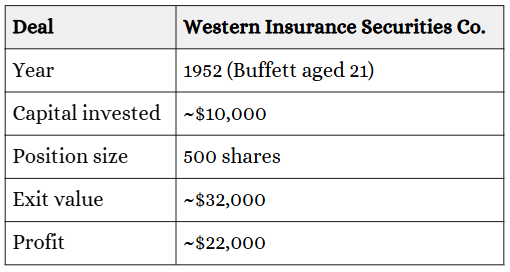

Western Insurance Securities Co.

Western Insurance was one of those rare cases where everything Buffett liked came together at the same time.

In early 1952, he had just graduated from Columbia, was working at his father’s brokerage in Omaha, and had a net worth of ~ $20,000.

He spent his days flipping through the Bank and Finance section of Moody’s Manual, looking for things other investors ignored.

That’s how he came across Western Insurance Securities.

Western was a small holding company that controlled two insurance businesses. Most of the premiums came from plain, boring auto insurance. Not very exciting. But the numbers were absurd.

The company had just 50,000 shares outstanding. Buffett said he was buying shares between $12 and $20. Using $20 as a conservative estimate, the entire company was valued at about $1,000,000.

Western had been profitable for a full decade. Premiums and market share had grown steadily since the company was founded in the 1920s, and its combined ratios were consistently better than the industry average.

The balance sheet was strong too. By 1951, Western had built up a large pool of investable assets from insurance float. Almost all of it was invested in conservative bonds. The investment income alone was more than enough to cover the dividends owed to preferred shareholders.

And then there was the valuation.

Western earned $940,000 in net income in 1951.

At a $1 million market value, Buffett was effectively buying the business at just 1.06 times earnings.

The setup was so compelling that he even sold GEICO to buy Western. That tells you a lot about his conviction. Western almost certainly became one of his largest positions, likely accounting for more than half of his capital.

Buffett later wrote about Western in The Security I Like Best in March 1953. By that time, the stock was already trading around $40.

Later that year, Western traded as high as $65.

In less than two years, Buffett turned roughly $10,000 into about $32,000. A gain of more than 225%.

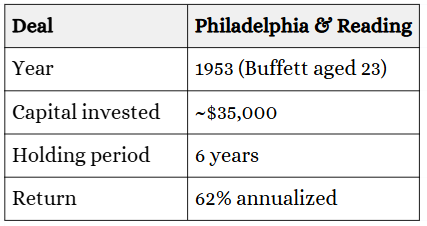

Philadelphia & Reading

Philadelphia & Reading looked like a terrible business on the surface.

It was an old producer of anthracite coal. By the early 1950s, anthracite was a dying market. Demand had been artificially inflated by a postwar boom, which allowed the company to do pretty well from 1946 onward. But by the early 1950s, it was losing to oil, gas, and other fuels.

But that’s not what Buffett focused on.

He started buying shares around 1953, near $19. When the stock fell to about $9, he bought more. By the end of 1954, he had invested roughly $35,000 and, once again, made it his largest position. At that point, Philadelphia & Reading accounted for about 35% of his net worth.

At prices around $13 to $14 per share at the end of 1954, the stock was trading close to its net current asset value and at less than half of book value. The per-share equity value stood at $32.

On top of that, the company owned large culm banks, piles of coal waste left over from earlier mining operations. Buffett believed these piles had hidden value as fuel and estimated they could be worth around $9 per share on their own. That provided an additional margin of safety.

But the real driver behind this investment was Graham.

He began buying shares in 1952, joined the board, and took control of the company in 1955. His goal was no longer to save a dying coal business. Instead, he wanted to turn a cheap, shrinking operation with large tax loss carryforwards into a capital allocation vehicle.

Over the next three years, Graham-Newman transformed Philadelphia & Reading from a rundown coal miner losing $3 million a year into a profitable holding company earning $7 million annually, with returns on equity of 17%.

The first big move was buying Union Underwear at a low price. Similar deals followed. Costs were cut, unprofitable operations were shut down, and even the coal assets were used strategically to return cash to shareholders in tax-efficient ways.

At a purchase price of $9 per share, Buffett effectively paid about 2.3 times 1956 earnings of $3.88. Adjusted for tax carryforwards, the multiple was closer to 1.3 times earnings on $7.06 per share. Earnings continued to grow, reaching $6.19 per share by 1958, while the valuation multiple expanded to around 15.

By early 1959, Philadelphia & Reading was trading above $100 per share.

Over his holding period, Buffett’s return likely worked out to roughly a 62% annualized return.

Meanwhile, Graham-Newman continued to build Philadelphia & Reading into a diversified holding company, acquiring businesses ranging from toy manufacturers to steel mills. In 1968, Graham and Newman ultimately sold the company to Northwest Industries.

Over their much longer holding period, Graham-Newman’s return came out to 18% per year.

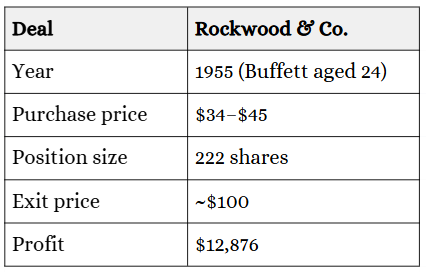

Rockwood & Co.

While working at Graham-Newman, Buffett spent most of his days digging through companies that other investors ignored. That’s how he came across Rockwood.

Rockwood was a manufacturer of chocolate bits and had a long history of losses. On the surface, it looked completely uninvestable.

But buried in the balance sheet was something that caught Buffett’s attention.

Rockwood owned a massive inventory of cocoa beans. Cocoa prices were high at the time, and the value of the inventory alone far exceeded the company’s market capitalization. The problem was taxes. If Rockwood simply sold the beans, roughly half of the gains would go to the government. That made a straightforward liquidation unattractive.

Graham-Newman was offered the chance to buy the company but passed. The asking price was too high for a classic Graham-style liquidation.

Instead, Jay Pritzker, another well-known investor, ended up taking control.

Pritzker found a way around the tax problem by using a rule that allowed partial liquidations without triggering the full tax burden. Rather than selling the beans for cash, Rockwood offered shareholders a deal: each share could be exchanged for $36 worth of cocoa beans. At the time, the stock traded at about $34.

That created a clean arbitrage.

Graham saw the opportunity and instructed a young Buffett to buy shares, tender them for cocoa, and then sell the beans. To remove price risk, Graham-Newman simultaneously hedged by selling cocoa futures.

They did this over and over again, week after week.

But Buffett noticed something else.

The exchange offer was fixed at 80 pounds of cocoa per share. Yet Rockwood owned far more cocoa than was implied by that offer across all outstanding shares. As shareholders tendered their stock, the remaining shareholders were left owning an ever-larger share of the company’s cocoa inventory.

So Buffett did something different from his employer. Instead of just running the arbitrage, he bought 222 shares for himself at an average price of about $42 and held them. In doing so, he effectively aligned himself with Pritzker, who understood exactly what was happening.

As the liquidation progressed and the value became obvious, the stock climbed to around $100.

Buffett made $58 a share vs. the $2 a share the arbitrageurs made.

In total, Buffett earned around $12,876 on his position.

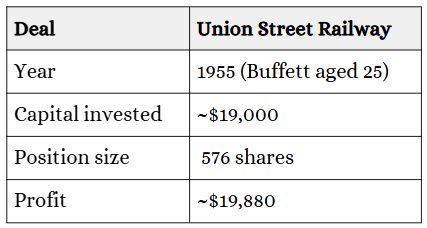

Union Street Railway

Union Street Railway was a tiny bus company based in New Bedford, Massachusetts.

Buffett first tried to place the idea with Graham-Newman. Graham looked at it but wasn’t willing to take a meaningful position. Buffett, however, thought the stock was far too cheap to ignore. So he bought it for himself.

By the time Buffett discovered it, the business was in long-term decline. Ridership was falling and the company had just posted losses. Nothing about the income statement was attractive.

The balance sheet was the entire thesis.

When Buffett started buying, Union Street traded between $30 and $35 per share, giving it a market capitalization of roughly $640,000. Yet the company held substantial hidden assets that pushed net cash to more than $60 per share.

Here’s how Buffett later described the situation, recalling it fifty years later:

“It had a hundred sixteen buses and a little amusement park at one time. I started buying the stock because they had eight hundred thousand dollars in treasury bonds, a couple of hundred thousand in cash, and outstanding bus tickets of ninety-six thousand dollars. Call it a million dollars, about sixty bucks a share. When I started buying it, the stock was selling around thirty or thirty-five bucks a share.”

Buffett didn’t need profits to recover. He only needed management to stop sitting on the cash.

Even though he had found a clear bargain, building a position wasn’t easy. Buffett had to run newspaper ads looking for shareholders willing to sell their shares.

By 1955, he was able to accumulate 576 shares, about 3% of the company. At the same time, Union Street was buying back stock, which increased his stake to more than 4%.

At that point, Buffett did something that was becoming a recurring pattern.

He got in the car and went to see management.

He drove overnight to New Bedford to meet the company’s president. The meeting was polite and uneventful until the very end, when the president casually mentioned that the board was considering a return of capital.

What he meant was a $50 special dividend.

On a stock Buffett had bought for $30 to $35.

After the $50 payout, the stock traded between $15 and $20 for the rest of 1956. Buffett had invested around $19,000, received $28,800 in cash, and still owned shares worth $10,080.

All in, his return was just over 100%.

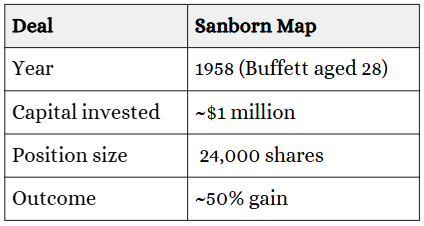

Sanborn Map

Sanborn Map Company was one of the first times Buffett was forced to move beyond passive deep value and into action.

At first glance, Sanborn looked like a bad business.

The company produced highly detailed fire insurance maps. For decades, this had been a wonderful model. Once a city was mapped, the same maps could be sold over and over again to insurance companies at almost no incremental cost. Margins were high, and for a long time there was little competition.

By the 1950s, that moat was eroding.

Insurance companies began using “carding,” an early form of statistical underwriting that reduced the need for physical maps. Demand declined steadily, and profits collapsed from more than $500,000 a year in the 1930s to roughly $100,000 by the late 1950s.

But Buffett did not buy Sanborn because he expected the map business to recover.

He bought it because he liked what he found on the balance sheet.

Over decades of strong profitability, Sanborn had accumulated a large portfolio of bonds and blue-chip stocks. These investments had originally cost about $2.6 million, but thanks to the postwar bull market, they were now worth roughly $7 million.

The entire company, however, was trading for about $4.7 million.

In other words, investors were paying seventy cents on the dollar for the investment portfolio and getting a still-profitable operating business thrown in for free.

Once again, Buffett went in heavily.

By late 1958, more than one-third of the partnership’s capital was invested in Sanborn. Shortly thereafter, Buffett owned enough shares to secure a seat on the board.

The board was dominated by representatives of insurance companies, Sanborn’s customers. They owned almost no stock themselves and had little incentive to maximize shareholder value.

Buffett proposed a simple solution: separate the operating map business from the investment portfolio so the value would become obvious to shareholders.

The board rejected it.

Buffett responded by buying more shares.

Eventually, the partnership owned nearly 23% of Sanborn. His associates owned another 21%. Together, they controlled more than 40% of the company.

At that point, Buffett had effective control.

Only then did the board give in.

More than a year after Buffett began buying shares, Sanborn offered shareholders the right to exchange their stock for a proportional slice of the investment portfolio. Shares trading around $45 could be exchanged for securities worth roughly $65.

The result was a gain of about 50% for Buffett’s partnerships.

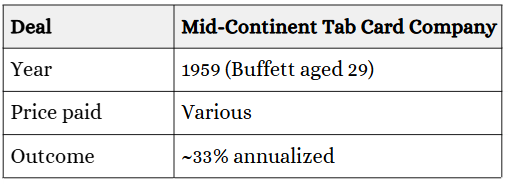

Mid-Continent Tab Card Company

Mid-Continent Tab Card Company is a great example of how Buffett actually thinks before he invests.

In 1958, two friends approached him with an idea. They wanted to compete with IBM in a small but highly profitable niche: punch cards. These cards were used to feed data into early computers. IBM dominated the market and earned enormous margins on them.

His friends believed they could compete because they were based in the Midwest and could ship faster.

Buffett knew IBM well. He had studied the company for years and believed its competitive position was overwhelming. A small start-up competing against IBM could fail fast. That single risk was enough for him to walk away.

He didn’t look at projections. He didn’t think about upside. He simply stopped thinking about the idea and rejected it.

His friends went ahead anyway. A year later, the business was printing 35 million tab cards a month.

IBM had not crushed them.

At that point, Buffett became interested again because the major risk he saw was gone. Only then did he start to reconsider the investment. And what he saw was extraordinary.

The company was turning its capital over seven times a year, earning net profit margins of around 40%, and growing more than 70% annually on $1 million of sales.

It was one of the most profitable companies Buffett had ever seen.

But even then, he did not project earnings ten years into the future. Instead, he asked himself if the cost advantage could last, if the business could keep reinvesting its profits at high returns, and if he could still earn a solid return if growth slowed down.

He invested about 20% of his net worth into the company. Over time, he added more as the business kept performing.

Mid-Continent later became Data Documents. Buffett held the company for nearly two decades. Throughout that period, it continued to reinvest, grow, and earn high returns on capital.

When it was finally sold in 1979, Buffett earned a 33% annual return on his original investment.

Learnings

After walking through these early investments, a few factors keep showing up that explain his outperformance. Things like a strong filter, deep research, high concentration, and, when needed, activism.

Importantly, these factors didn’t work on their own. They worked together and formed a single, self-reinforcing system.

(1) Everything starts with a strong filter.

Buffett spent endless hours going through thousands of stocks. He was very quick to dismiss bad ideas to be efficient in his screening and research process.

He could decide not to invest in something in as little as two minutes. If he spotted a major risk early on, he stopped thinking about the idea altogether and moved on.

Mid-Continent Tab Card Company is a good example. When the idea was first presented to him, Buffett didn’t start with upside scenarios or earnings projections. He began looking at what could go wrong with the investment. As soon as he identified a major risk, he forgot about it and didn’t waste another thought on it.

Only later, when that risk was gone and the business had proven it could survive, did he return and investigate the company further.

This ability to say “no” quickly allowed Buffett to conserve mental energy and spend his time only on ideas that were truly worth it.

(2) What followed was extreme research.

Buffett wanted to know everything. Not just what showed up in the financial statements, but how the company actually worked, who ran it, and what kind of people they were.

He didn’t shy away from extra effort. He skipped classes to attend Marshall-Wells’ shareholder meetings. He took a train from New York to Washington just to knock on GEICO’s door. He drove overnight to New Bedford to meet Union Street Railway’s president.

Alice Schroeder describes this perfectly in The Snowball:

“In his classic investments he expends a lot of energy checking out details and ferreting out nuggets of information, way beyond the balance sheet. He would go back and look at the company’s history in depth for decades. He used to pay people to attend shareholder meetings and ask questions for him. He checked out the personal lives of people who ran companies he invested in. He wanted to know about their financial status, their personal habits, what motivated them.”

Once the work was done and Buffett knew enough about a company and had sufficient conviction, he sized accordingly.

(3) Conviction led to concentration.

Buffett ran a highly concentrated portfolio.

It was not unusual for a single position to make up 20% of his capital. And when he was really sure about something, he had no problem going even further.

Buffett said many times that he didn’t necessarily have more good ideas than other investors. He simply had fewer bad ones and focused as much as possible on his best ideas.

This is also evident in the investments covered above.

He made GEICO 75% of his portfolio.

Philadelphia & Reading was about a third.

Western Insurance likely more than half.

Sanborn Maps over 20%.

And Mid-Continent Tab Card around 20%.

Even during his Berkshire years, it was not unusual for five stocks to make up 75% of the total holdings.

(4) Activism, when needed.

Because his positions were so large, Buffett didn’t shy away from influencing outcomes when it mattered.

He wasn’t a fan of activism. But when value was locked up and management stood in the way, he was willing to step in.

Take Sanborn Maps, for example. Buffett took control, forced a change in capital allocation, and closed the gap between price and value. That single situation accounted for a large share of his profits in 1960.

The key insight is that all of those factors work together.

A strong filter leads to the few ideas worth extreme research.

Extreme research creates conviction and reduces risk.

Strong conviction allows high concentration.

High concentration produces extraordinary results and, when necessary, the ability to influence outcomes and unlock value.

That loop is a key reason behind Buffett’s early outperformance. And it’s something worth studying if you want to become a better investor.

Lastly, if you enjoyed this deep dive into Buffett’s early years and want to explore even more case studies, I can highly recommend the book “Buffett’s Early Investments.” It covers several other early investments in much greater detail and reaches a similar conclusion.

Disclaimer: This content is provided for informational and educational purposes only and does not constitute financial, investment, legal, or tax advice. I am not a registered investment advisor or broker. Nothing written here should be relied upon to make investment decisions. Always conduct your own research and consult with a qualified financial advisor before investing. I may or may not hold positions in the securities discussed, and that may change without notice. Any mention of a company, security, or strategy should not be interpreted as a recommendation to buy, sell, or hold. Investing in securities involves substantial risk, including the risk of total loss. Past performance does not guarantee future results. While I make reasonable efforts to ensure the accuracy of information, I cannot guarantee that the content is complete, accurate, or up to date. I accept no liability for any loss or damage arising from reliance on this content.

A fantastic article - I've never seen as much information on this topic!

Funnily enough, I went to the Berkshire AM about 15 years ago

and got to ask a question - I tried to pump Buffett for information on

pretty much this topic (my question was something like could he give

some particular examples of times in his career when he put a very large

percentage into one investment). Buffett's response wasn't that informative,

but this one was worth waiting 15 years for!

Very insightful breakdown, thanks Noel. Position sizing is arguably more important than hit rate. Something I'm still figuring out!