How Charlie Munger Made 3,000% in Two Years

A Case Study.

It’s well known that Charlie Munger had a big influence on Warren Buffett’s investing style.

Before meeting Munger, Buffett was a pure Graham-style investor. Only buying cheap “cigar-butt” stocks trading far below intrinsic value, hoping for a quick gain.

Through Munger, that changed.

He began to care less about buying at the lowest price and more about buying great businesses at fair prices. Munger believed that quality and long-term durability mattered more than short-term bargains.

But Charlie himself didn’t always follow that rule.

In his early years, he often bought “lousy” or average businesses simply because they were very cheap, and the opportunity was too good to ignore.

In a 2016 interview, he even said that he and Warren would still do the same today if the price was right:

„If a marketable security was available on a horribly mispriced basis in some lousy business, I think we might still buy it. If things are cheap enough, it gets the juices flowing.“

Today’s story is about one of those cigar-butt investments Charlie made back in the 1970s.

A stock so cheap that he ended up making about 32 times his money in under two years. And yet, despite that incredible return, he still calls it one of the biggest mistakes of his life.

Belridge Oil Co.

Belridge Oil was a small pink-sheet company that owned rich oil fields in California. It was founded in 1911 by the Green, Whittier, and Buck families, whose descendants still held majority control decades later.

What made Belridge special was the way it owned its land.

Unlike most oil companies, it didn’t lease land, it owned all the ground it was drilling on. And that land was sitting on roughly 376 million barrels of oil, producing about 40,000 barrels a day.

As Charlie Munger later described it in 2014:

„It was just an incredible oil field that was going to last a long time, and it had very interesting secondary and tertiary recovery possibilities and they owned the whole field to do whatever they wanted with it. That’s rare, too.“

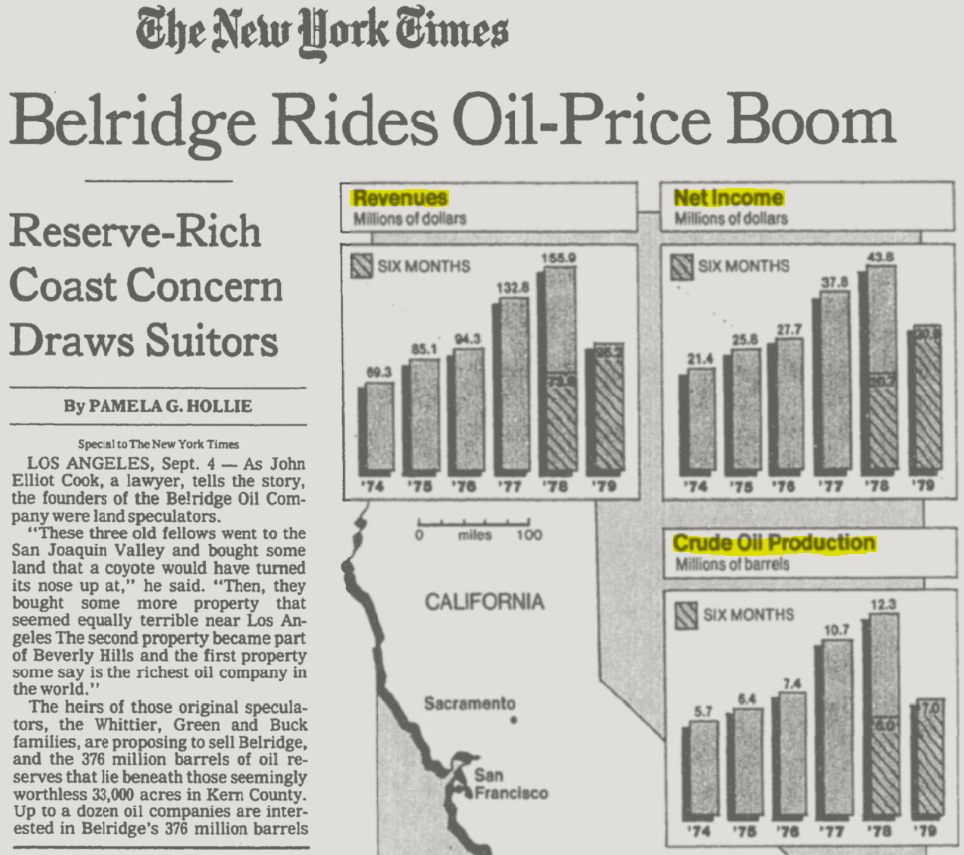

During the 1970s, the company was performing extremely well. A mix of higher oil prices and new extraction technology helped Belridge more than double its production and income in just five years.

Because most of its wells were classified as “stripper” properties, Belridge was exempt from federal price controls on crude oil.

That meant it could sell its oil at full market prices, sometimes earning $11 to $16 a barrel while competitors received barely half of that.

Belridge has used the earnings from the higher prices to expand production. By 1978, Belridge was producing over 40,000 barrels a day, up from just 16,000 barrels in 1974.

The financial results reflected this growth:

Revenue grew from $69 million in 1974 to $156 million in 1978, and profits more than doubled to $44 million.

Dividends climbed from $5 a share in 1974 to $21 in 1978 for the 550 shareholders of the company’s nearly one million shares.

This strong performance was highlighted in a 1979 New York Times article:

The New York Times, September 5, 1979

The Investment

In 1977, Charlie Munger got a call from a friendly broker.

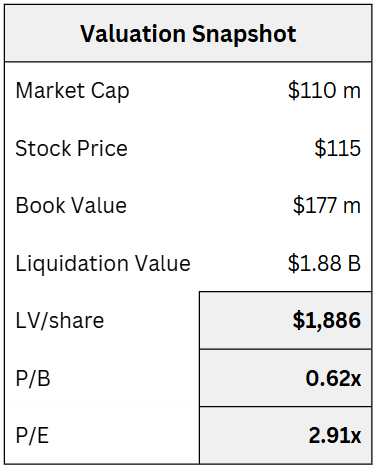

The broker offered him 300 shares of Belridge Oil at a price of $115 each.

On the surface, Belridge was just kind of a cheap-looking oil stock.

It was a small, illiquid company with a market cap of about $110 million and a book value of $177 million. So it traded at a modest discount to book value and at about 3 times earnings.

But according to Charlie, what really made the investment stand out were the things you didn’t see on the balance sheet, the assets hidden under the ground.

Belridge owned all its land in California, and that land held around 376 million barrels of oil.

At the time, oil was selling for five to six dollars per barrel.

That meant the true liquidation value of Belridge was closer to $1.88 billion, not $110 million.

In other words, the market was valuing the oil at only 29 cents per barrel.

For Charlie, this was a simple, straightforward asset play.

29 cents versus five or six dollars per barrel is clearly quite a large discrepancy. He was basically being offered a profitable, growing, high-dividend business for about 6 percent of its liquidation value.

That’s about as complicated as the investment thesis got.

So of course he bought the 300 shares for a total investment of $34,500.

Here’s what Charlie said about Belridge Oil at the 2001 Berkshire meeting:

“When I was somewhat younger, I was offered 300 shares of Belridge Oil. An idiot could have told me there was no possibility of losing money and a large possibility of making money. I bought it.”

And he wasn’t exaggerating.

Even if the oil never reached full market value, the margin of safety was enormous. Using a very conservative estimate, say $2 to $3 per barrel, the liquidation value still came out between $750 million and $1 billion.

That still implied an upside of 7 to 9 times the market cap.

The Outcome

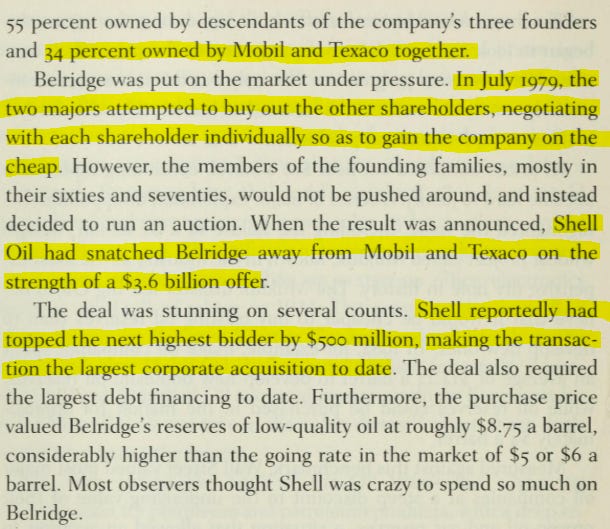

In 1979, the two other major holders of Belridge Oil, Mobil and Texaco, tried to take control of the company.

They didn’t launch a fair, open offer. Instead, they went from shareholder to shareholder, trying to buy the company cheaply.

The founding families did not like this at all.

So they put Belridge up for auction, which started a full-on bidding war among the biggest oil companies in America.

Ultimately, Shell was the highest bidder, outbidding the next-highest offer by $500M, and bought the entire company for $3.6 billion, one of the largest takeover deals in American history at that time.

Big deal: mergers and acquisitions in the digital age, by Bruce Wasserstein, p. 214.

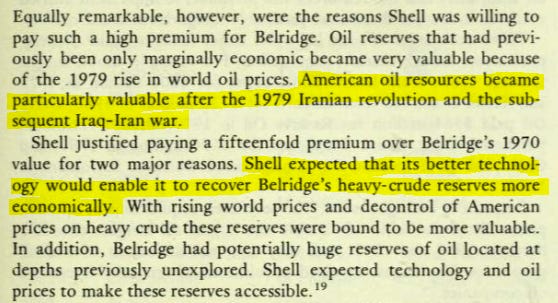

Shell saw huge potential for more production from the Belridge field. They expected the amount of oil in the ground to be even larger than the 376 million barrels of proven reserves and hoped to raise output significantly. So they didn’t hesitate to pay 82x earnings.

A staggering valuation, but it was worth it.

Since then, Shell has extracted over $60 billion worth of oil from the Belridge fields, and those wells are still producing today.

Mega-mergers: corporate America’s billion-dollar takeovers, by Kenneth M. Davidson, p. 254.

Now, remembering that Charlie Munger paid $115 per share, the sale price came out to $3,665 per share, or about eight dollars per barrel of oil.

That’s a 31.9x return, or about 3,087%.

Munger’s $34,500 investment clearly did very well. It turned into just under $1.1 million, a serious amount of money for Charlie at the time.

Reflections

If you bought a stock and made 32 times your money in only two years, I’m going to take a wild guess that you’d feel pretty happy.

Yet at the 2001 Berkshire Hathaway annual meeting, when Warren Buffett and Charlie Munger were asked about their biggest investment mistakes, Charlie actually brought up Belridge Oil.

Judging by the outcome, the mistake wasn’t in his investment thesis. It clearly worked out very well.

The mistake was not betting big enough when he had a no-brainer investment opportunity presented to him.

See, just days after the broker first offered him 300 shares, he called again.

This time he offered Charlie 1,500 more shares at the same price of $115. Buying them would have required roughly $172,500.

And Charlie actually turned them down.

At the 2001 Berkshire meeting, he explained why:

“The guy called me back three days later and offered me 1,500 more shares. But this time I had to sell something to buy the damn Belridge Oil. That mistake, if you trace it through, has cost me 200 million dollars. And it was all because I had to go to a slight inconvenience and sell something.”

He knew it was a great deal.

He knew it was a no-brainer.

He was offered the shares at the same bargain price… and yet he turned it down.

Simply because he had to go through the inconvenience of selling something else.

That tiny moment of hesitation turned into one of the biggest opportunity-cost mistakes I’ve ever seen.

By not putting an additional $172,000 to work, a position that would have turned into roughly 5.5 million, he didn’t just miss the profit from Belridge. He missed the far larger compounding that would have happened afterward.

A lot of Charlie’s Belridge profits were actually rolled into his initial purchases of Berkshire Hathaway shares.

Had he taken that second block of shares, it would have given him enough cash to buy around 21,114 additional Berkshire Class A shares, back when they traded at about 260 dollars each.

Those shares today would be worth billions.

So Charlie’s regret wasn’t making the investment, it was not betting big enough.

I want to end this with another quote from Charlie, where he explains what we can learn from his mistake:

„You don’t get that many great opportunities in a lifetime. When life finally gave me one, I blew it. So I tell you that story to say you’re no different from me. You’re not going to get that many really good ones - don’t blow your opportunities.”

I hope you enjoyed it.

Disclaimer: This content is provided for informational and educational purposes only and does not constitute financial, investment, legal, or tax advice. I am not a registered investment advisor or broker. Nothing written here should be relied upon to make investment decisions. Always conduct your own research and consult with a qualified financial advisor before investing. I may or may not hold positions in the securities discussed, and that may change without notice. Any mention of a company, security, or strategy should not be interpreted as a recommendation to buy, sell, or hold. Investing in securities involves substantial risk, including the risk of total loss. Past performance does not guarantee future results. While I make reasonable efforts to ensure the accuracy of information, I cannot guarantee that the content is complete, accurate, or up to date. I accept no liability for any loss or damage arising from reliance on this content.

3000% return in 2 years - ok, you’ve got my attention…

That's the one! I look forward to reading it carrry on with the good work 👍🏽