You Don’t Need a Catalyst

And a net-net trading below net cash

Most stock pitches you read always include some kind of upcoming catalyst. I mean, even ValueInvestorsClub requires every pitch to have one.

But only investing in stocks with a clear catalyst kind of defeats the purpose of value investing.

Catalysts are not important, nor are they required for an investment.

Don’t take it from me. Take it from the man who defined value investing, Ben Graham. He just wanted one thing:

Cheap stocks.

Warren Buffett also wants to buy one thing:

Great businesses.

Michael Burry searched every corner of the market for:

Value. Deep Value.

None of them ever wrote about needing a catalyst to make an investment work. In fact, they told you the opposite.

Sit and wait, they said.

I remember when I first read Burry’s old write-ups on VIC (you can still find them here) I was stunned. As a “catalyst,” he often wrote: “Sheer value.”

That really stuck with me. And the more I thought about it, the more it made sense.

Because when we talk about catalysts, what we’re really doing is trying to guess what will eventually change other investors’ minds about a stock. And that’s a tough game to play.

We’re basically trying to predict an event and how others will react to it.

The problem is, we’re bad at predicting the future. And we’re even worse at predicting how other investors will respond.

The desire to find a catalyst probably comes from our bias towards believing that current trends will continue. So when we see a stock sitting below NCAV for years, we feel like there has to be some special trigger to change that.

Sometimes, yes, it’s reasonable. When you’re looking at a micro level, and a company is selling undervalued assets, that can clearly unlock value. Fair enough.

But once you start making grand projections like: “I think U.S. stocks will underperform because X will happen”, it becomes more complicated. The more complex the story, the less reliable it is.

In part, the obsession with a catalyst is a time horizon issue.

If you’re investing for the long term, you don’t need to know what specific catalyst will change the outcome. You can simply wait for the fundamentals to do their work (assuming you are right).

If you’re investing short term, sentiment matters more. You’re basically guessing how other investors will behave. And for that, yes, you need a catalyst. (That’s why short-term investing is so hard)

Even in hindsight it’s often hard to point to the exact reason why sentiment changed. For sure we can tell a great (and simple) story as to why something has happened, but the truth is always more complicated.

So if we can’t even get it right with the benefit of hindsight, trying to do it with foresight is probably unwise.

If you must seek a catalyst, remember that being cheap itself is a catalyst. It’s the number one catalyst, that always gets ignored simply because it’s too boring.

Walter Schloss used to say:

“If you buy low enough, something good may happen to you.“

So let Mr. Market do his thing.

Is a catalyst nice to have?

Sure.

Is it necessary?

No.

Here's what you need

Now, to be clear, even though I don’t specifically look for a catalyst, I do think about the possibility of one.

If a stock is cheap, others will notice sooner or later. Whether it's management, investors, or competitors, someone will get interested. The company might become a takeover target.

That’s something I like to keep in mind, because that could act as a catalyst in the future.

But when you buy into that certainty, when you pay up for a near-term catalyst, you’re paying a premium.

In 1979, Warren Buffett said “You pay a very high price for a cheery consensus.“ You also pay a very high price for a guaranteed catalyst.

Which brings me to Deswell Industries.

A tiny net-net I wrote about 6 month ago.

The absence of a catalyst was what made this stock cheap.

As is usually the case. If you want to buy really cheap stocks, you need to get comfortable owning stocks without a catalyst.

Most investors hate the idea of not having an “exit strategy.” But really an investor (rather than a trader) should be a person who doesn't need an exit strategy. A value investor should be able to accept a really low price instead of a catalyst.

They don’t need an exit strategy.

They just need a margin of safety.

DSWL

DSWL is a perfect example of what I mean.

When I first wrote about DSWL, it was a net-net trading at just 3.6x earnings and about 50% below NCAV.

It was a classic, overlooked compounder that most investors had overlooked.

When I researched the stock, I could hardly find any analysis at all. It wasn’t mentioned on Twitter, barely anywhere really.

Which means there was no way I would have ever just “stumbled” across it. If I hadn’t found it myself, I probably never would have heard of it.

That’s also why I spend so much time just going through random tickers, one by one. I set broad filters on my screener and flip through everything.

I found that to be the only real way to find uncovered stocks.

Deswell itself is a global operator doing essential pre-production work, like plastic injection molding, circuit board assembly, wireless receivers, that sort of thing.

When I found them, they had a market cap of about $36.97M and reported net income of $10.34m. They had $96.11M in current assets, $74.85M NCAV, and a long track record of paying a dividend every single year for more than two decades.

Since then, nothing has really changed. The numbers have improved a little, but nothing extraordinary.

There was no catalyst.

No buybacks, no spin-off, no big asset sale.

And yet… the stock rallied more than 100% over the last four months.

Why?

Because Mr. Market decided to reprice it.

Other investors saw the opportunity, bought in, and pushed the stock higher.

That’s all it was. The market correcting an inefficiency.

See, the point of value investing isn’t that the market is completely inefficient. It’s that the market tends to be inefficient in smaller pockets.

And while the market makes mistakes, it’s still efficient enough to eventually correct them.

That’s exactly what happened with Deswell.

Granted, it happened fast. It’s only been six months since I wrote about it, and the stock is already up more than 80%.

Usually, moves like that take time. If a stock doubles in three years, giving me an average CAGR of around 25%, I’m happy.

Even if it takes five years, that’s still ~15% a year.

This also shows something important. It takes time for stocks to return back toward fair value. Sometimes months, sometimes years. And that’s perfectly fine, that’s how value investing works.

You buy stocks below fair value, and then you wait. Wait for the market to do its thing.

So there’s no need to get nervous if a stock hasn’t moved after six months. And there’s definitely no need to check the price every day.

A net-net trading below net cash.

There’s another stock I’ve had on my watchlist for a while. I haven’t invested in it yet, not because I don’t like the business, but simply because I found other opportunities more attractive at the time.

But it’s still a great example of what I’m talking about. It’s net-net trading far below intrinsic value, with no clear catalyst.

The company is called Everybody Loves Languages Corp. ($ELL).

It’s a tiny Canadian EdTech business focused on language learning.

The model basically has two pillars:

The SaaS side, with digital learning platforms, online courses, and apps. Even though multiple languages are offered, English is the main focus. Most of the revenue here comes from licensing and subscriptions.

The focus may be on the growing SaaS business, but the second pillar still makes up the larger share of revenue (66%). This is the content-based publishing business in China that originally shaped ELL. Here, language-learning books, CDs, and materials for the Chinese education market are produced and distributed. ELL acts as a co-publisher and receives royalties on the sales.

Revenue is pretty steady at around C$2.4m a year. With a market cap of just C$1.6m and net income of about C$0.3m, they’re trading at only 6.7x earnings.

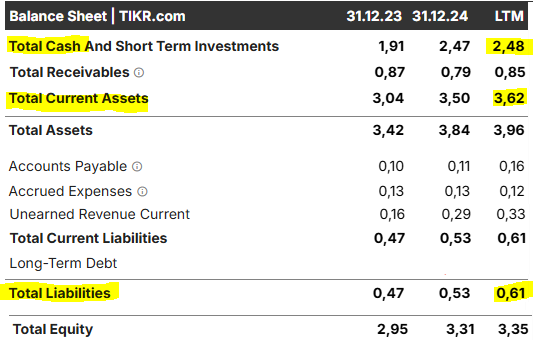

Where it really gets interesting is the balance sheet. They trade at 53% of NCAV and even below net cash. And since they don’t carry any intangibles, the numbers are pretty clean.

Now, to be clear, this isn’t meant as a full deep dive on ELL. I’m working on another stock right now. I just wanted to share this in the context of this piece, because it’s a perfect example of a cheap stock without a catalyst.

Even without a catalyst, a valuation like this naturally creates opportunities. A business trading below net cash, profitable, not shrinking its balance sheet, makes it a potential acquisition target. Whether it’s investors, competitors, or management itself, someone is going to notice.

That way, value itself becomes the catalyst. Nothing else is needed.

To sum it up

I’ve found that stocks where you know the next year won’t look much different are often the ones that end up mispriced.

In other words, mispricings usually show up when your time horizon is longer than everyone else’s.

In fact, I’d say it’s one of the best signals to dig deeper into a stock, when people tell you: “Sure, it’s a fine business, safe and all, but I just don’t see what’s going to move it in the next year or two.”

That’s the perfect time for you to research the stock.

Disclaimer: This content is for informational and educational purposes only and should not be considered investment advice. I’m just sharing my thoughts—not telling you what to do with your money. Some of what I write may turn out to be wrong. Always do your own research.

Fully agree. Thanks for this post, Noel.

Just a warning, I did some work into everybody loves languages, a lot of that cash is tied up in JV / Subsidiary’s they don’t fully own, but are fully consolidated on their balance sheet