How Buffett Bought a Dollar for Thirty Cents

His little-known 1950s bet on Union Street Railway

It’s no secret that Warren Buffett is one of the greatest investors of all time - perhaps the greatest.

Over the past 60 years, he compounded at an average rate of 20% per year and turned Berkshire Hathaway into one of the most successful investment stories ever told.

Some people also know about his earlier years, when he ran Buffett Partnership Ltd. and compounded at around 30% annually throughout the 1950s and 60s.

But his trades before that, the ones he made in the early 1950s, are widely unknown.

Even though those were the times when Buffett was managing just a few thousand dollars and compounded at more than 50% per year.

Those are the trades I find most fascinating. Because they show what’s possible when you’re managing a small capital base - let’s say, under $1 million - and have the time to do some digging.

With less capital, Buffett could fish in smaller ponds. And the opportunities he found were often wildly mispriced.

Like the one in this story, where he found a tiny business trading below net cash.

It may not have been a high-quality company, but it was a classic cigar butt, and Buffett made a killing off it.

Union Street Railway

Union Street Railway was a New Bedford, Massachusetts–based bus company trading below its net cash position, and at just 25% of tangible book value, when Buffett discovered it.

It was a tiny, illiquid nanocap with a market cap of under $1 million, roughly $11 million in today’s dollars.

Because of the small float and lack of liquidity, he couldn’t just log into a brokerage account and buy some shares.

It took real effort to acquire a stake in the company.

But as we’ll see, the effort paid off.

The Business Behind the Bargain

Union Street Railway operated a local public transportation system, primarily using buses, across southeastern Massachusetts.

1947 Union Street Railway Bus

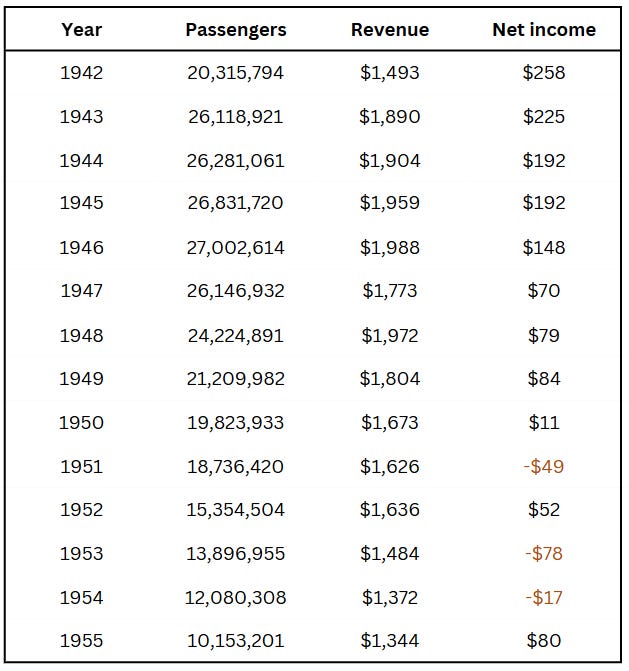

During the 1940s, especially throughout World War II, the company benefited from government restrictions on private travel and was able to generate steady profits thanks to booming passenger numbers.

It remained profitable throughout the decade and built up a substantial cash position.

After the war, though, ridership steadily declined, especially as more people bought private cars. Revenues and earnings dropped, and the company began posting losses.

Despite the negative results in the early 1950s, Union Street remained operational, owning a valuable fleet of more than 110 buses and serving several cities in the region.

Still, the decline in passenger numbers, revenue, and profitability caused the stock to sell off hard. It dropped so far that the market valuation fell below the company’s net cash position.

In other words, the stock was priced as if the business were already dead, even though it was still a functioning, if shrinking, operation.

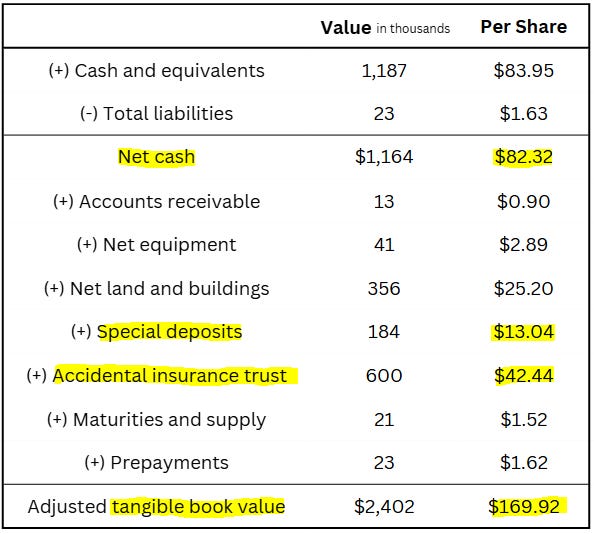

Source: Moody’s Manuals. Dollar figures in thousands.

Finding Dollars for 30 Cents

For Buffett, the setup was clear: He was buying a functioning business that traded for less than its net cash.

At the time, Union Street Railway had a market cap of just $640,000 and an enterprise value of $325,000.

In other words, it was tiny.

Here’s what Buffett said about the investment, recalling it fifty years later:

„It had a hundred sixteen buses and a little amusement park at one time. I started buying the stock because they had eight hundred thousand dollars in treasury bonds, a couple of hundred thousand in cash, and outstanding bus tickets of ninety-six thousand dollars. Call it a million dollars, about sixty bucks a share. When I started buying it, the stock was selling around thirty or thirty-five bucks a share.“

Pretty remarkable how sharp his memory is, that he could recall the reasoning in such detail half a century later.

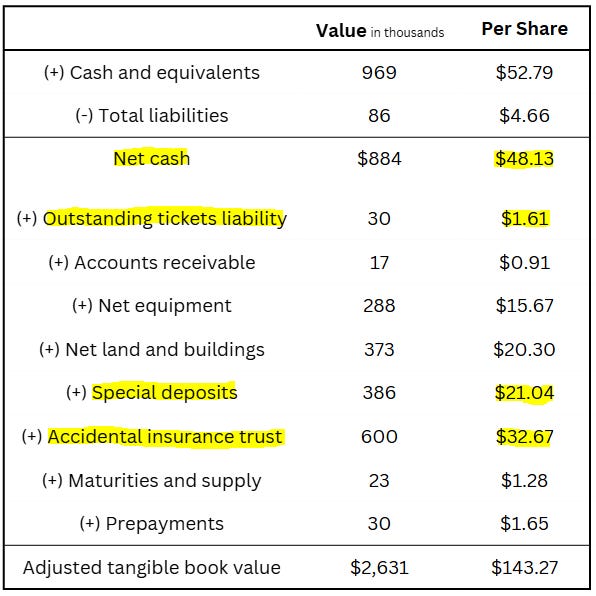

Anyway, here’s a quick snapshot of the balance sheet Buffett was looking at at the time:

Source: Moody’s Manuals.

As you can see, trading at $30 to $35 a share, the stock was already selling at a steep discount to net cash.

But there was more to it than just cash.

As Buffett pointed out, the company had also issued a batch of bus tickets. Sold, but unused.

Rightfully, the business accounted for these as a liability, since they represented deferred revenue: the company had received the cash but hadn’t yet delivered the service.

Still, Buffett noticed, the value of that liability hadn’t changed from 1952 to 1953.

So he figured those tickets were probably never going to be used.

And even if they were, the marginal cost of an additional passenger was practically zero, as no cash expenditure would have to be incurred if the passenger used the ticket.

So he mentally wrote off the liability and treated the cash as earned, adding another $1.61 per share to his valuation.

Then came the long-term assets: “Special deposits” and an “insurance trust.”

Those were basically just tied-up cash, expected to be released over time. Together, these two items added another $53.70 per share of value.

Altogether, that brought Buffett’s estimate of cash to $103.44 per share. For a stock he was buying at $30 to $35.

He was effectively buying a dollar for thirty cents, and getting a functioning business on top.

That’s some textbook value investing right there.

While the company posted a net loss in 1953, Buffett wasn’t too worried. He knew they could adjust operating expenses to match demand, by cutting routes or tweaking the service. So Union Street wasn’t likely to just burn through the cash.

So the stock was obviously a bargain.

Anyone who looked at the balance sheet could tell the stock was dirt cheap.

But the company was tiny and hard to find. And that’s exactly where Buffett had an edge.

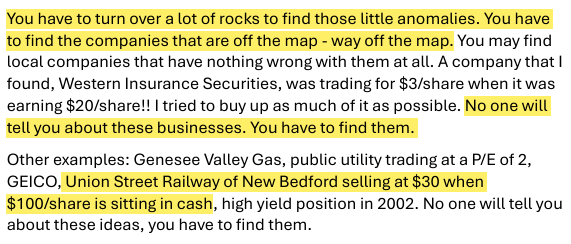

Here’s what he later told students at the University of Kansas:

How Buffett Built His Stake

Even though he had found a clear bargain, building up a position turned out to be a real challenge.

Because the stock was so illiquid, even Buffett, with a net worth of just $100,000 at the time, had to get creative to find enough shares to build a meaningful stake.

So he launched an ad campaign in the local newspaper, hoping to find shareholders willing to sell.

But the company wasn’t stupid either.

They knew the stock was cheap. So they ran competing ads. Making it harder for Buffett to find holders who were willing to sell him their shares.

But eventually, with some effort, he was able to buy 576 shares, totaling a 3.1% stake in the company.

Then Things Got Even Better

Thanks to Union Street’s repurchasing program, Buffett got a nice bonus: As the total share count shrank, his 576 shares now made up 4.1% of the business.

At the same time, Union Street converted some of its “special deposits” into liquid cash and decreased liabilities by writing off the unused bus tickets, which boosted their already strong net cash position even further.

The good news continued, as the company returned to profitability in 1955, earning $5.70 per share.

As a result, the stock rose quickly, trading between $50 and $61 that year, still only 73% of net cash and 35% of tangible book value.

Here’s what the updated balance sheet probably looked like:

Source: Moody’s Manuals.

When Buffett eventually met with the company’s president, Mark Duff, he got more news he liked:

“By the way, we’ve been thinking of having a ‘return of capital’ distribution to shareholders.” – Mark Duff

He wasn’t talking about a modest little dividend with a 6% yield. No, to Buffett’s delight, they were about to declare a fifty-dollar special dividend!

On a stock Buffett had bought for $30 to $35.

After the $50 payout, the stock traded between $15 and $20 for the rest of 1956.

While Buffett’s exact sale date isn’t public, it’s known that he held the stock at least through the end of 1956. Still convinced it was a good deal, with hidden assets left on the books.

It’s Easier Than It Looks

Even though the outcome of this investment was outstanding, the analysis behind it was surprisingly simple.

Any investor with a basic understanding of balance sheets and an eye for value could have spotted how incredibly cheap this stock was.

What made the difference was Buffett’s relentless research and his willingness to dig.

Without that, he would’ve never even found the opportunity.

Still, this trade didn’t work just because the discount was so steep. It worked because management did the right thing and returned excess cash to shareholders.

Union Street had been trading below net cash for years. Without the repurchases and the massive $50 dividend, the outcome would’ve been very different.

If we’re being conservative and assume Buffett bought in 1954 for $35, then received the $50 distribution and sold sometime in 1957 when the stock traded between $20 and $28, he more than doubled his money in just a few years.

This shows what’s possible when you’re managing a small amount of capital and are willing to put in the work to find these opportunities.

Sure, it takes effort. But the payoff can be massive.

And it's not impossible. I’ve seen plenty of people, even on here, compounding at rates that most hedge fund managers would envy.

Disclaimer: This content is for informational and educational purposes only and should not be considered investment advice. I’m just sharing my thoughts—not telling you what to do with your money. Some of what I write may turn out to be wrong. Always do your own research.

Interesting story! Thank you for sharing, Noel! It looks like this position was about 20% of his portfolio. Solid bet.