How a Young Michael Burry Earned a 143.7% IRR

Revisiting his 2001 investment in GTSI Corp.

Before the fame, and long before the housing market trade, Michael Burry was a young investor searching for value in small and overlooked corners of the market.

He spent his time turning over rocks, looking for bargain-priced stocks, and sharing his ideas on his blog and on Value Investors Club.

One of those ideas was a small government IT distributor called GTSI.

Compared to the positions he would later take in his career, this was a relatively small trade.

Still, it offers a lot to learn.

It shows how he thought about entering a position, what he saw in the business, and why he ultimately decided to exit.

The investment turned out to be quite successful, generating an IRR of 143.7%. But the return isn’t the main point.

The process is.

So let’s rewind to March 28, 2001.

The day a 29-year-old Michael Burry shared this idea on Value Investors Club.

GTSI Corp.

He opened his write-up like this:

„A debt-free net-net stock, now showing earnings growth and consistency for the first time.“

Which already hinted at why the stock caught his attention.

GTSI was a technology distributor focused almost entirely on government customers. It supplied computers, software, and networking equipment to the U.S. military, the IRS, and other federal agencies.

In other words, it was a classic B2G business. The company was based in Chantilly, Virginia, just outside Washington, D.C.

It was a low-margin business by nature.

GTSI competed for large contracts against much bigger players, including firms like IBM. What allowed it to survive, and eventually thrive, were long-standing relationships inside the government procurement system.

In addition, GTSI was one of the first firms to move into e-commerce. In the early 1990s, the company launched GTSI Online (gtsi.com), an electronic catalog and ordering system. Through this platform, government agencies could search products, place orders, and process purchases electronically using EDI systems.

Their website looked like this:

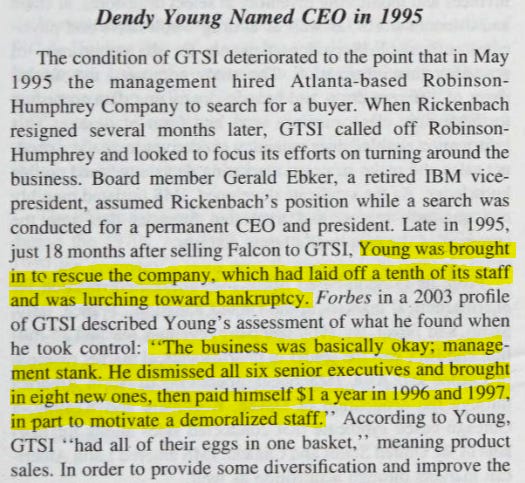

Four years before Burry wrote about the company, new management had taken over and started turning around what had previously been a money-losing operation. They improved working capital discipline and inventory turnover.

As a result, the business slowly became more efficient.

International Directory of Company Histories, Vol. 57 (2004), p. 172

By the time Burry was looking at the stock, the turnaround was clearly visible in the numbers.

GTSI had been profitable for the third consecutive year, gross margins were starting to improve, revenue had grown from $486 million to $678 million in just four years, and retained earnings were compounding quickly, doubling in the prior year alone.

In fact, the company earned as much money in that year as it had in its entire previous history combined.

In addition, the company was buying back shares. Executives were purchasing stock in the open market. Even employees were buying small amounts on their own.

Outside of his VIC write-up, Burry also discussed GTSI in his MSN articles. There, he described it as:

“one of the cheapest stocks in my universe, with the best story.”

Let’s look at the numbers to see why.

The Numbers

Since this isn’t a case study from the 1960s, there’s no need to dig through old Moody’s manuals to find the numbers.

The annual and quarterly reports are still available online through the SEC.

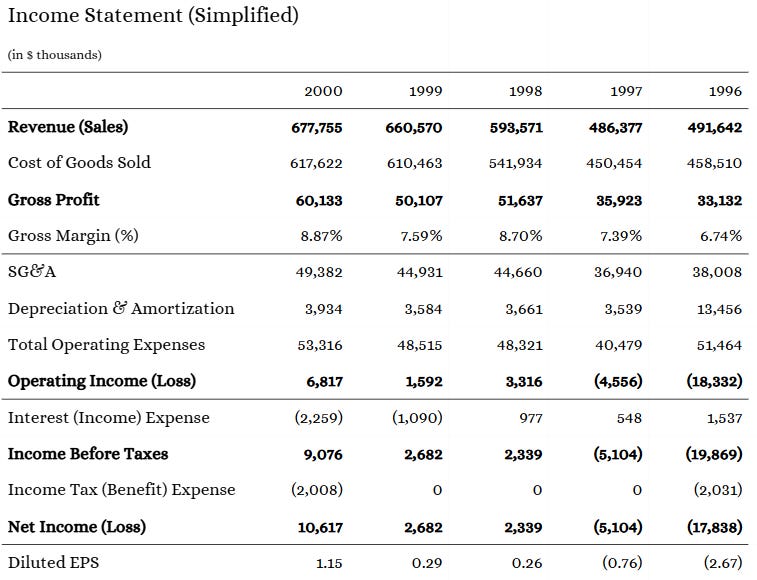

Below is a simplified version of the financials Burry was looking at when he analyzed the stock.

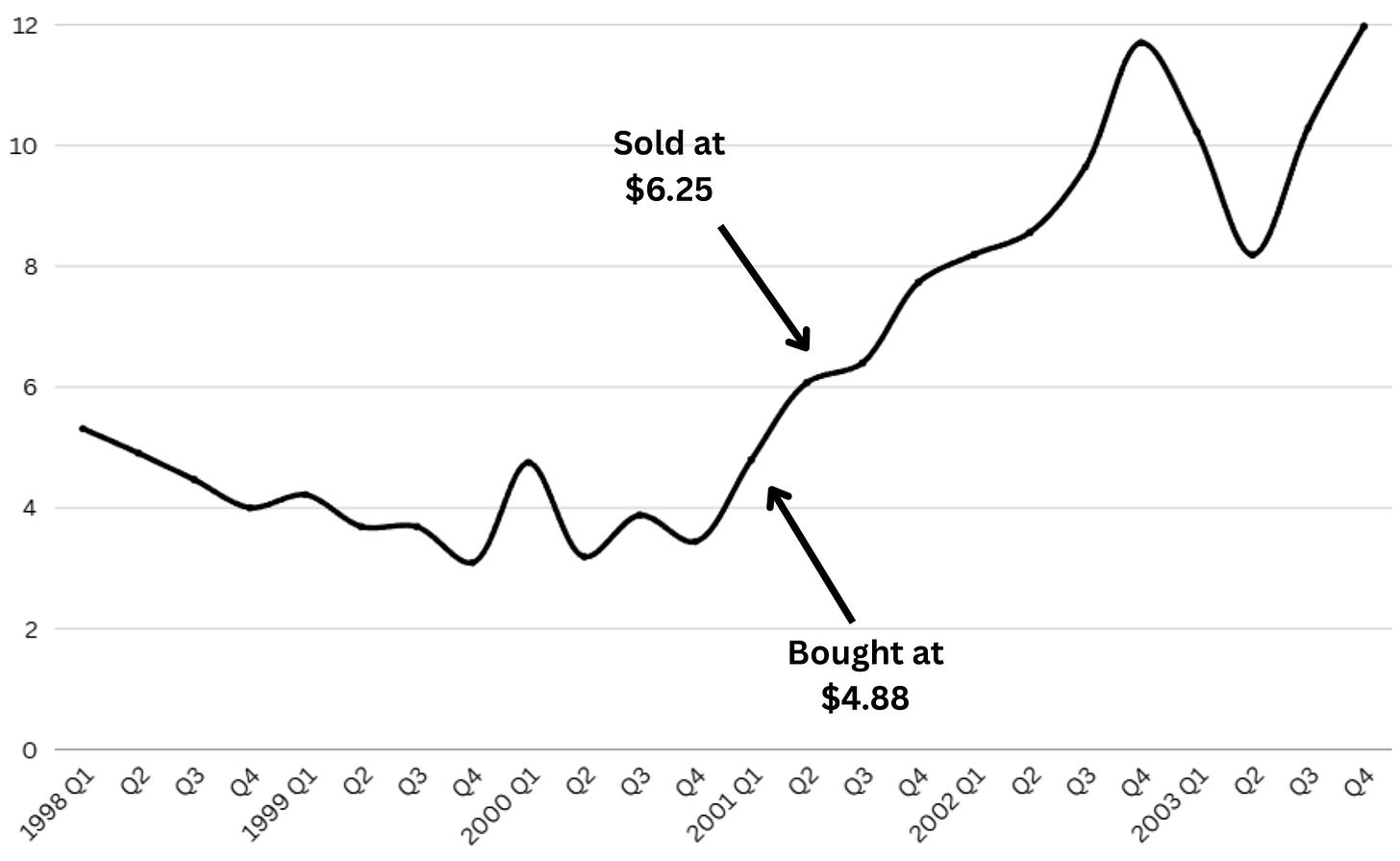

I don’t know the exact share price at the moment he wrote the VIC post. In his MSN articles, Burry mentioned placing buy orders at $4.88. In the VIC write-up, he referred to the stock trading around $5. Maybe he rounded. It’s unclear.

To keep things simple, let’s use $5.

At the time, GTSI had 8,130,481 shares outstanding. At $5 per share, that put the company’s market cap at $40.65 million.

Just like Burry pointed out, the numbers leading into 2001 were clearly improving, with net earnings reaching an all-time high of $10.6 million.

That means the stock was trading at just 3.83x earnings.

Even if you adjust for the tax benefit and look at a more “honest” earnings number, the P/E was still only around 4.5.

Combine that with capable management, a business that was improving, no meaningful debt, and active share buybacks, and you pretty much have a dream setup.

At this point, you might ask: how does an opportunity like this even exist?

Honestly, I would have wanted to buy it too.

Burry addressed exactly that in the comments to his VIC write-up.

He wrote:

“The stock is cheap because it is illiquid and no one is paying attention.”

That sentence says almost everything.

It shows that these kinds of opportunities existed for the same reason they existed in Buffett’s time, why they still exist today, and why they probably always will.

Some corners of the market are simply ignored. They get forgotten and overlooked. And that’s where inefficiencies form.

A quick side note on the “net-net” label

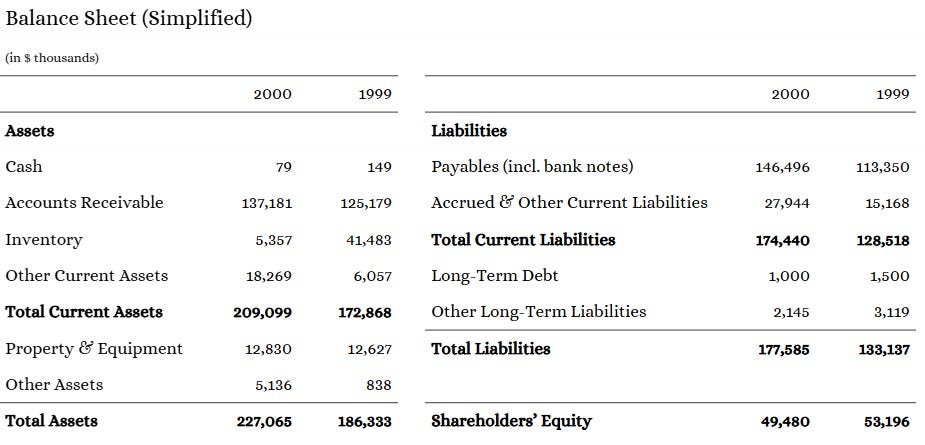

At the beginning of his VIC write-up, Burry referred to GTSI as a net-net. But if you look at the balance sheet at the time, total net current asset value was about $31.5 million:

Compared to a market cap of ~$40 million, GTSI was not actually trading below NCAV. It did trade below book value, but that alone doesn’t make a stock a net-net.

So why did Burry call it one?

Well, he explained this later in the comments.

Before the write-up, the stock had been highly volatile. It often traded down to 2/3 of NCAV, then rallied back toward full NCAV.

Even though the stock was obscure, some value investors were aware of it. Each time it dipped deep below NCAV, they bought it in classic Graham fashion and sold once it reached what they considered fair value, hence creating a kind of trading range in the stock.

Apparently, Burry himself was one of the investors profiting from this behavior. As he wrote:

„The trading strategy with this stock has always been to buy just under 3 and wait for a spike - there have been a few - and sell it.“

In the VIC comments, he explained that this was why he still thought of GTSI as a net-net. Even though it no longer qualified as one at the time of his write-up, he kept using the label out of habit.

The Trade

I almost have to split this trade into two parts.

Thanks to Burry’s MSN articles, I have clear data on his buying and selling activity during 2001.

But, and this is an important but, in his VIC write-up, he mentioned that he had already been buying the stock a year earlier, in 2000, at prices around $3.

„It would not be surprising if pre-tax income starts to approximate the share price myself and others paid back in the $3 range last year. (…). I’m still accumulating the stock.“

Unfortunately, there is no precise data on those earlier purchases. I could guess when he bought and how much, but that wouldn’t be honest. So I’ll focus on the part of the trade where we have clear, documented evidence: 2001.

Burry placed his first order on March 9, 2001. It was a limit order to buy 1,400 shares at $4.75.

“March 9, 2001

Buy 1,400 shares of GTSI Corp. at 4 3/4 limit, good until cancelled.”

Based on what followed, it’s reasonable to assume that this order was either not filled at all or only partially filled.

A few days later, on March 16, Burry wrote: “Let’s adjust a few unexecuted trades,” and changed the order.

“March 16, 2001

Change the outstanding limit order on GTSI Corp. to buy 1,500 at 4 7/8 limit, good until canceled.”

Then, on March 29, he added another order:

“March 29, 2001

Place order to buy 500 shares of GTSI Corp. at 4 7/8 limit, good until canceled.”

If we assume that the first limit order was not filled, Burry ended up buying 2,000 shares at $4.88.

That puts the total position size at $9,760.

The stock moved quickly after that. Within just a few months, it was trading above $6.

And on June 29, 2001, Burry placed a sell order for his entire position at $6.25.

“June 29, 2001

Sell all shares of GTSI at 6.25 limit, good until cancelled.”

My guess is that Burry initially planned to hold the stock longer.

In his MSN articles, he wrote:

“I believe the stock is worth at least 8 and probably more.”

At $6.25, the stock hadn’t even reached his estimate of fair value.

So why did he sell so early?

Here is how he explained it:

“My job is to take advantage of market inefficiency. (…) These quirks in the market can be used to great advantage, especially by individual investors.”

“The reason I’m willing to sell into such spikes, if they occur, is that spikes are spikes. What goes up on a temporary imbalance comes down when the imbalance resolves.”

At $6.25, the total profit on the 2001 portion of the trade was about $2,740.

It may not sound like much at first, but you have to put it into perspective.

That’s a 28.1% return in a little over three months.

On an annualized basis, that works out to 143.7%.

And that only reflects the 2001 purchases. The true absolute return was likely much higher, given that Burry had already been buying shares in the $3 range a year earlier.

Interestingly, the stock continued to rise after his exit and eventually moved well past his estimate of fair value.

Revenue and operating income kept improving, and the share price followed.

GTSI reached a high of $14.89 in the fourth quarter of 2002.

I wasn’t able to find a price chart going back that far. But I reconstructed a rough price range using the highs and lows disclosed in the annual and quarterly reports.

The chart isn’t perfectly precise, but it’s good enough to give a sense of how the stock behaved after Burry’s purchase.

Learnings

The one thing Burry was always looking for was value.

Uncovered, overlooked, mispriced value.

He didn’t need a specific catalyst. If a stock was cheap enough, value itself became the catalyst.

That’s exactly what played out here. He bought the stock at a valuation that was low enough and waited for the market to correct its own inefficiency. In this case, that correction came sooner rather than later.

Even though this was a relatively small trade for him, with a total position size of just about $10,000 (if we only look at the 2001 purchases), it still says a lot about his qualities as a stock picker and how deep his understanding of valuation and market behavior really was.

In hindsight, it feels like a subtle preview of what was still to come.

Just like in my last write-up on Burry’s strategy, I want to end this one with his own words:

“In the end, investing is neither science nor art — it is a scientific art.”

I hope you enjoyed it.

Disclaimer: This content is provided for informational and educational purposes only and does not constitute financial, investment, legal, or tax advice. I am not a registered investment advisor or broker. Nothing written here should be relied upon to make investment decisions. Always conduct your own research and consult with a qualified financial advisor before investing. I may or may not hold positions in the securities discussed, and that may change without notice. Any mention of a company, security, or strategy should not be interpreted as a recommendation to buy, sell, or hold. Investing in securities involves substantial risk, including the risk of total loss. Past performance does not guarantee future results. While I make reasonable efforts to ensure the accuracy of information, I cannot guarantee that the content is complete, accurate, or up to date. I accept no liability for any loss or damage arising from reliance on this content.