A Stock Buffett Would Buy

A classic net-net trading at 4.6x earnings and 0.48x book value

Key Metrics:

4.6x earnings

0.48x book value

38 consecutive years of dividends

Over 50% of market cap in cash

Undervalued real estate held at historical cost

If Warren Buffett had to pick a favorite type of stock from his early days, it would probably be this one.

Net-nets.

They were the backbone of his early investing success. A strategy he learned from Benjamin Graham and executed with incredible results.

Buffett used to call them “cigar butts.”

Cigar butts, because they’re not exactly appealing, but still very profitable. While these are not the kind of businesses you’d want to hold forever, they're selling so cheaply relative to what they’re worth, buying them is like picking up a nearly finished cigar off the sidewalk.

It costs nothing to pick up, so those last couple of puffs are pure profit.

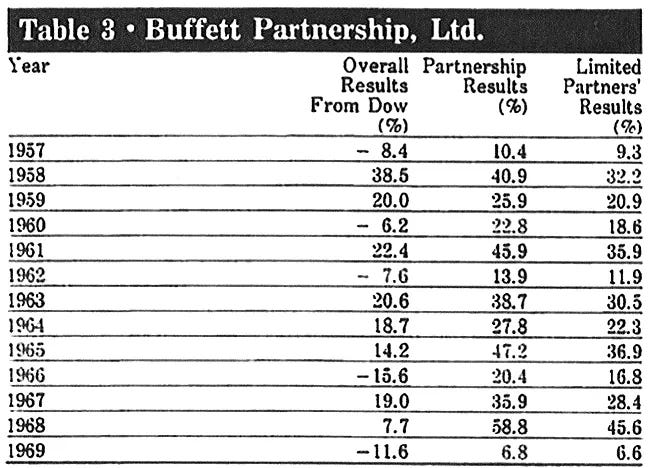

“The many dozens of free puffs I obtained in the 1950s made that decade by far the best of my life for both relative and absolute investment performance.” – Warren Buffett

Here is an overview of his performance during this period:

What’s a net-net anyway?

Essentially, a net-net stock is a stock with a low price-to-book ratio, but with all long-term assets stripped from book value.

That’s probably the easiest way to explain it.

Why strip away long-term assets?

Because that turns book value into what net-net investors call Net Current Asset Value (NCAV).

By focusing only on the NCAV, you’re calculating a very conservative estimate of what the company would be worth if it were liquidated tomorrow.

When Benjamin Graham developed the strategy back in the 1930s, he found that NCAV was often a solid proxy for a company’s real-world liquidation value.

Often, entire businesses were bought for a price roughly equal to the company’s NCAV. And when a company was completely liquidated, shareholders received an amount close to the company’s NCAV per share.

Whatever losses might have come from writing down the current assets were often made up by the long-term assets, which were excluded from the original calculation.

The formula for calculating a company's NCAV is really straightforward:

NCAV = Cash + Accounts Receivable + Inventory - Total Liabilities

So if it’s that simple and profitable, why isn’t everyone doing it?

Of course, no investing method is perfect. For one, net-net stocks – at least the ones with positive earnings and a dividend, trading at a steep enough discount– can be very hard to find under normal market conditions.

At any given time, there might only be 5 to 10 truly investable net-nets if you’re only looking at the U.S. market.

You’ll find more if you look internationally, places like London, Toronto, Frankfurt, or Tokyo.

But even then, finding them takes a lot of work.

That’s probably one of the biggest reasons why most retail investors don’t pursue this strategy more aggressively.

Most people simply don’t have the time. They have jobs, families, other priorities, and combing through obscure reports for overlooked stocks isn’t exactly a casual hobby.

But for those willing to dig, the reward can be worth it. Because when you buy below liquidation value, you’re not betting on a story, you’re buying assets for less than they’re worth.

It’s one of the most time-tested and proven strategies to outperform the market. And pretty much no other strategy offers returns as consistently great as net-net stock investing.

And today’s stock?

It’s one of those rare finds. A quiet little net-net company trading below its net current asset value, profitable, with a strong balance sheet and a 38-year dividend history.

Let me walk you through it.