A Family Business for 40 Cents on the Dollar

5x earnings. 57% discount to NCAV.

Key Metrics:

5x earnings

57% discount to liquidation value

No debt

Norbert Lou is one of those lesser-known investors. His name doesn’t carry the weight of Warren Buffett, Joel Greenblatt, or Michael Burry. And yet, among value investors, he’s highly respected.

If you’ve been in the investing game for a while, you’ve probably heard of him.

His fame may not match theirs, but his returns clearly do.

From 1994 to 2003 he compounded at 38.5% per year - starting with $60,000 of his mother’s retirement money.

He began sharing his write-ups as “charlie479” on Value Investors Club.

One of the people who noticed was Joel Greenblatt, who later helped him launch his own fund and contributed $10 million.

In July 2001, Lou wrote about a tiny business called Winmill & Co. Incorporated.

It’s a family-run investment management firm in upstate New York with a market cap back then of just $2.8 million.

His pitch was simple.

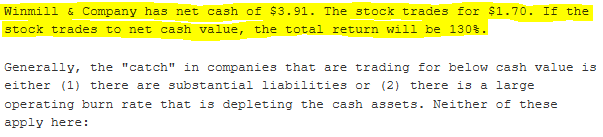

At $1.70 per share, the company sold for 45% of its net cash. The business was mediocre, but it was dirt cheap.

Within three years, the stock soared to $4.75 per share.

But the story didn’t end there.

In 2004, Winmill stopped filing reports with the SEC and essentially disappeared into the dark.

For a while, only the most obsessive deep-value investors even knew it existed.

Some of them managed to dig up hidden reports buried on Winmill’s website.

Nate Tobik from Oddball Stocks was one of them.

Using the Google machine in a clever way, he discovered PDFs with names like annualreport2007.pdf hidden on their site. He wrote about the stock in 2013.

But eventually, those reports stopped too.

The stock sank to the bottom, while shareholders must have wondered what the company was up to.

The price fell to $0.53, valuing the whole business at just $751,941.

Fast forward to today.

Lou now runs his fund, Punch Card Capital, and manages more than $500 million.

And Winmill has come back into the light. In 2023, the company started filing audited annual reports again, retroactive to 2021.

And once again, the stock is dirt cheap.

Let’s take a closer look.

Income Statement

Winmill & Co. makes its money by managing and marketing a handful of funds. Revenue comes from management and distribution fees.

Specifically, Winmill provides investment management and distribution for the two mutual funds in the Midas family, as well as investment management for the closed-end fund Foxby Corp.

Now, fund management is a pretty good business model. You’ve got a steady stream of annual fees, all based on a percentage of assets under management.

Which means revenue scales directly with AUM.

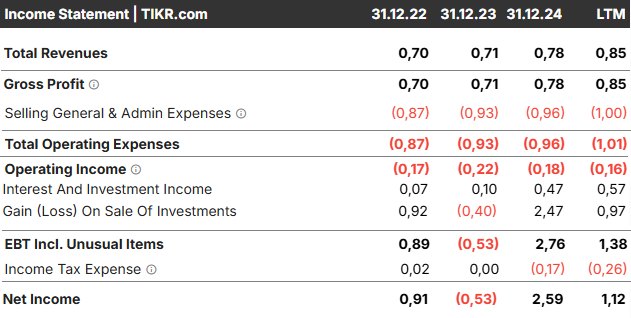

You can see that in Winmill’s topline numbers, which climbed from about $700k to $850k in the LTM.

However, their operating business actually loses money every year.

The reason net income still shows black ink is their investment portfolio gains, which have been big enough to offset the operating loss and push the company into profit.

In the last twelve months, net income was $1.12m. At today’s price, that puts the stock at just 5x earnings.

That’s attractive on its own, no doubt.

But let me be clear: this is not the thesis.

The real story here is on the balance sheet, in the assets they hold and the discount the market gives them relative to liquidation value.

It’s actually very similar to the situation Norbert Lou pointed out more than 20 years ago.

Balance Sheet

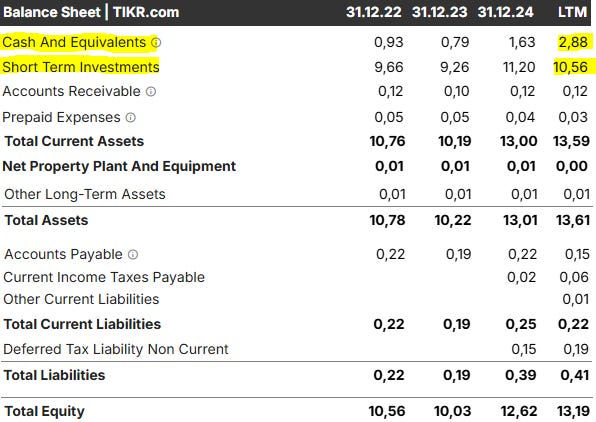

As of July 30, 2025, Winmill has $2.88m in cash and $10.56m in investments held at fair value.

That’s basically all of their assets.

The liability side is almost nothing. Just $0.41m.

That leaves net current asset value at $13.18m, or $9.23 per share. With a market cap of $5.68 million and a stock price of $4, that’s about 130% upside to liquidation value.

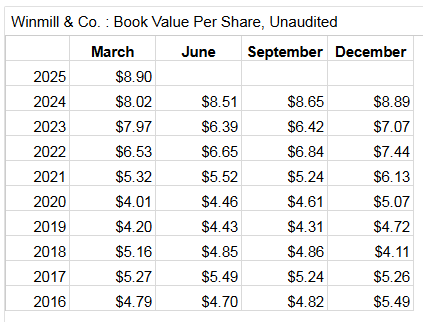

I also like that their total equity keeps growing.

This is literally their stated goal. They mention this pretty much everywhere they can:

„The objective of Winmill & Co. Incorporated is to increase book value per share over time for the benefit of its stockholders.“

Here are their book value numbers over the past decade:

Now, let’s take a closer look at their investments. There is more to it.

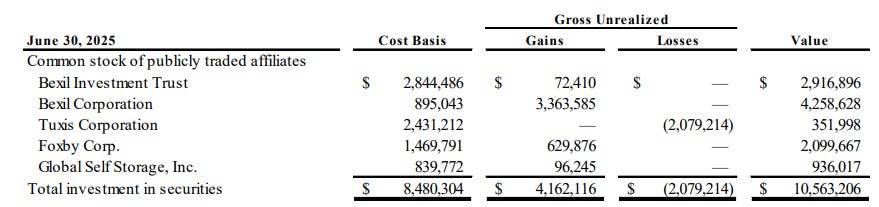

These are their current holdings:

They own 2% of Bexil, 19% of Tuxis, 24% of Foxby, and 2% of Global.

All of these are investment management firms in one way or another. Foxby is even their own fund. Winmill both manages it and owns shares in it.

Now, these aren’t just random stock picks. Members of the Winmill family sit on the boards of all of these companies and exercise varying degrees of control.

Over the years, they’ve built this web of cross-holdings that makes the whole structure tough to untangle.

But it gets even more interesting. Most of these holdings are trading below net asset values themselves.

Bexil and Foxby both trade at about a 30% discount to NAV.

Tuxis trades at just 0.28x book.

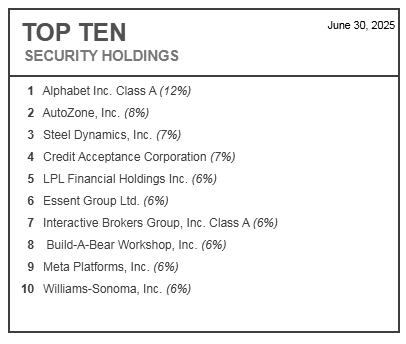

And it’s not like they have particularly risky investments. Foxby and Bexil both have some exposure to metals and mining companies. But aside from that, their portfolios are filled with fairly standard holdings.

Here are Foxby’s top 10 positions (funny enough, 9 out of 10 are identical to Bexil’s):

So what you’re really getting is undervalued assets, inside of an already undervalued wrapper. A discount on top of a discount.

A classic “value within value” setup.

The Value Trap Question

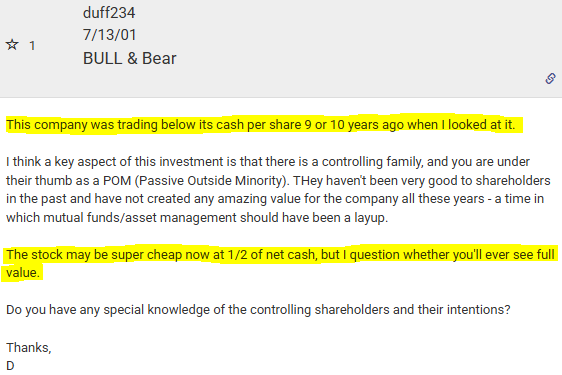

When I read through these old writeups on Winmill, there was a common theme.

Almost all of them had the same thesis I have right now: the business is trading significantly below liquidation value.

And in the comments, there was always at least one person saying something like: “I looked at this a few years ago and it was the same back then.”

Even under Lou’s write-up 20+ years ago, someone wrote that the company was cheap 10 years earlier.

So you’re looking at a stock that might have been cheap for 30+ years.

Not exactly comforting.

Mind you, this is a comment from 2001.

My first thought was: is this just a straight-up value trap? I don’t want to own a stock that’s been cheap for ages.

And I bet you wouldn’t either.

But then I dug a little deeper.

Turns out, in 2006 the stock actually ran up to about $5 a share, right when its liquidation value was $5.06.

In other words, it did close the gap.

That’s important. It shows that the stock can close the discount. It’s happened before.

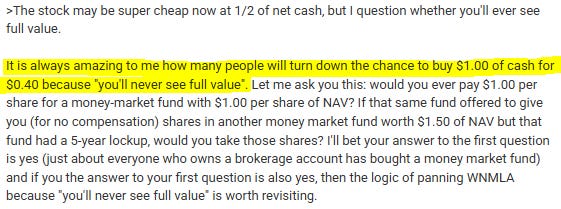

By the way, Lou himself gave a great answer to that same concern in the VIC comments. Worth a read:

I guess he was right.

Back to today

The reason it’s cheap again is much simpler.

Winmill went dark in 2004. Aside from the occasional hidden PDF report dropped on their website (think “annualreport2007.pdf”), there was zero shareholder communication.

Eventually, even those stopped.

The share price collapsed. And Winmill became a cigar butt all over again.

They started filing again in 2023. Publishing audited reports retroactively for 2021 and onward.

My best guess is that not many people have noticed the opportunity yet. It’s a tiny business, easy to overlook, and very few people even realize they’re back to reporting.

Give it some time, and other deep-value investors will eventually sniff it out. When they do, the discount should close again. As long as they don’t go dark a second time.

Shareholder structure

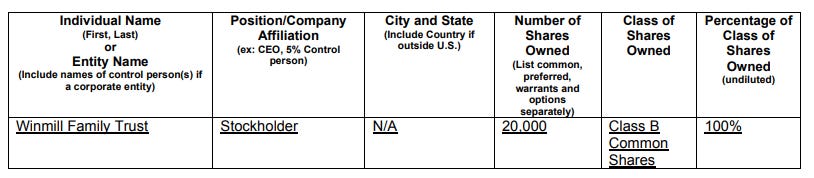

One last thing worth knowing: There are 1,398,758 Class A shares outstanding and 20,000 shares of Class B.

The two classes are identical except that only the Class B shares carry voting rights.

All of those are held by the Winmill family.

So you can buy Class A shares and effectively own the business alongside them, but you don’t get a say in how it’s run.

Final thoughts

I usually don’t like financial companies. They’re messy, they’re hard to value, and as Buffett says, better avoided most of the time.

But this one was so undervalued it caught my attention. The math is simple, you can basically buy a dollar for 43 cents. That’s a clear bargain.

And then there’s the fact that they started filing again. Why would they do that after almost two decades in the dark? There has to be a reason. Maybe they want the market to recognize full value. Maybe they’re preparing the business for a sale. Who knows.

Either way, I’ll close with the words of Norbert Lou, written in the VIC comments more than 20 years ago:

„I think the main focus of the idea is the incredible margin of safety versus assets that are liquid within an entity that is free of obligations and cash burn.“

Couldn’t have said it better.

Legend.

Disclaimer: This content is provided for informational and educational purposes only and does not constitute financial, investment, legal, or tax advice. I am not a registered investment advisor or broker. Nothing written here should be relied upon to make investment decisions. Always conduct your own research and consult with a qualified financial advisor before investing. I may or may not hold positions in the securities discussed, and that may change without notice. Any mention of a company, security, or strategy should not be interpreted as a recommendation to buy, sell, or hold. Investing in securities involves substantial risk, including the risk of total loss. Past performance does not guarantee future results. While I make reasonable efforts to ensure the accuracy of information, I cannot guarantee that the content is complete, accurate, or up to date. I accept no liability for any loss or damage arising from reliance on this content.

I'm sold. Glad I can finally buy them now! Good write up. We think much alike!

Nice find, Noel!